Endometriosis is a chronic, inflammatory, gynecologic condition affecting approximately 10% of individuals assigned female at birth, worldwide. The disease is marked by estrogen-dependent, progesterone-resistant endometrial-like tissue implants residing outside of the uterus, so-called endometrial lesions [1]. Pronounced symptoms of endometriosis are heavy menstrual bleeding, infertility, and pelvic pain and discomfort, often triggered by sexual intercourse, urination, or bowel movements. In addition to reproductive symptoms, the patient may present with other non-specific symptoms of fatigue, depression, nausea and vomiting, sleep disturbances, and dizziness [2]. The clinical features profoundly influence the life of someone who suffers from endometriosis negatively, affecting the quality of life, daily activities, physical and sexual functions, relationships, education and work productivity, and mental health well-being [3]. It remains unknown why endometriosis develops, but multiple genetic, immunological, and environmental factors seem to contribute to the manifestation of the disease [4]. The variety of symptoms and their different presentation lead to challenging and delayed identification of the condition, with an average wait for a diagnosis of 7-9 years globally, having a socioeconomic burden similar to type 2 diabetes. Throughout the patient’s journey, the condition is managed with painkillers and estrogen-suppressing medication, normally insufficient for symptomatic relief [5].

Today, endometriosis is diagnosed based on suspicion of disease concluded from the combination of symptoms, clinical findings, and imaging methods including transvaginal ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging. For a definitive diagnosis, laparoscopy with confirmative histology is considered the gold standard. It is also the only radical treatment method for endometriosis [6]. The post-surgical success of laparoscopy treatment outcome is highly dependent on the pre-operative findings in ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging, especially in identifying the subtype of deep endometriosis. Unfortunately, ultrasound does not meet the level of anatomical overview and resolution to give a complete picture of the disease’s spread. Similarly, magnetic resonance imaging is of limited use for surgical planning because of its highly varying accuracy, especially for visualizing smaller areas of deep endometriosis [7]. Of note, there is no contrast agent specifically approved for selective enhancement of such lesions. After a laparoscopic surgery to excise endometriosis lesions, repeated surgeries are normally needed as remaining endometriotic lesions that were not identified for removal will continue to grow [8].

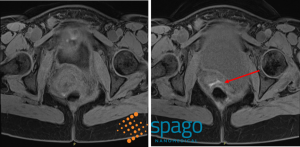

The clinical study SPAGOPIX-02 [9] explored the contrast-enhancing efficacy of the manganese-based contrast agent Pegfosimer manganese in participants with suspected endometriosis. The study was run in Sweden at one of the Swedish National Endometriosis Centres of Excellence in collaboration with world-leading radiologists and gynecolosists specialized in deep endometriosis. The study results show that the T1-weighted MRI sequences were of diagnostic value to assess enhanced active endometriosis lesions (Figure 1). The use of Pegfosimer manganese in MRI could lead to improved evaluation and pre-surgical staging of endometriosis extent, which is ultimately crucial for successful surgical outcomes and reduced recurrence of debilitating symptoms of this painful disease.

Figure 1: T1-weighted Dixon Magnetic resonance image sequences of transvaginal ultrasound-confirmed intravaginal endometriosis infiltrating the rectal wall, pre- (Left) and 2 hours post-infusion (Right) with Pegfosimer manganese contrast agent.

References

[1] Horne, Andrew W, and Stacey A Missmer. “Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis.” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 379 e070750. 14 Nov. 2022, doi:10.1136/bmj-2022-070750

[2] Saunders, Philippa T K, and Andrew W Horne. “Endometriosis: Etiology, pathobiology, and therapeutic prospects.” Cell vol. 184,11 (2021): 2807-2824. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2021.04.041

[3] Missmer, Stacey A et al. “Impact of Endometriosis on Life-Course Potential: A Narrative Review.” International journal of general medicine vol. 14 9-25. 7 Jan. 2021, doi:10.2147/IJGM.S261139

[4] Cousins, Fiona L et al. “New concepts on the etiology of endometriosis.” The journal of obstetrics and gynaecology research vol. 49,4 (2023): 1090-1105. doi:10.1111/jog.15549

[5] Saunders, Philippa T K et al. “Endometriosis: Improvements and challenges in diagnosis and symptom management.” Cell reports. Medicine vol. 5,6 (2024): 101596. doi:10.1016/j.xcrm.2024.101596

[ 6] Bafort, Celine et al. “Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis.” The Cochrane database of systematic reviews vol. 10,10 CD011031. 23 Oct. 2020, doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011031.pub3

[7] Abrao, Mauricio S et al. “Comparison between clinical examination, transvaginal sonography and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis.” Human reproduction (Oxford, England) vol. 22,12 (2007): 3092-7. doi:10.1093/humrep/dem187

[8] Nirgianakis, Konstantinos et al. “Recurrence Patterns after Surgery in Patients with Different Endometriosis Subtypes: A Long-Term Hospital-Based Cohort Study.” Journal of clinical medicine vol. 9,2 496. 11 Feb. 2020, doi:10.3390/jcm9020496

[9] ClinicalTrials.gov [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US). 2000 Feb 29 – . Identifier NCT05664828, Efficacy of SN132D in Patients With Suspected Endometriosis; 2022 Nov 17 [cited 2024 Oct 24]; https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05664828?term=sn132d&rank=1